- Home

- Twinkle Khanna

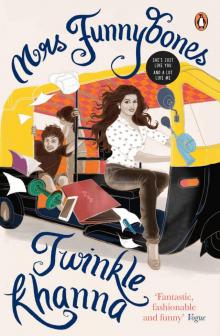

Mrs Funnybones: She's just like You and a lot like Me Page 6

Mrs Funnybones: She's just like You and a lot like Me Read online

Page 6

6.30 p.m.: Riding my yellow scooter back to our rented cottage, with the wind blowing through my hair and an orange and purple sunset setting the sky ablaze, my perfect day is almost over; only to do everything again the next day and the next, for as many days as the whim strikes us.

2014

Miss D and I are now grown women. We have amassed four children, two husbands and three dogs between the two of us, and over coffee we start talking about our old group, reminiscing about our past escapades and adventures with the boys and then we realize that none of these boys (now middle-aged men) are married.

Just for the record, these are all straight, financially solvent men; so to unravel their mysterious bachelorhood and to thoroughly entertain ourselves in the bargain, we decide to don our Sherlock and Dr Watson hats and investigate the matter.

Whipping out our phones and putting them on speaker mode, we start our unrehearsed phone questionnaires, which go a bit like this . . .

Me: ‘Hey, what’s up? A quick question and then you can go back to dealing with the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai: Why are you not married?’

Bachelor No. 1: ‘Are you nuts? You forgot I am divorced? None of you liked my wife, kept complaining that she smells of methi.’

I hastily disconnect the phone and call the next candidate on our list.

Me: ‘Hi! Quick question, why have you never been married?’

Bachelor: ‘Oh God! I think you have pressed redial because I have already given you that answer, now can I go back to earning a living?’

Oops . . .

We eat a few more chocolate biscuits, and my willing accomplice calls the next candidate.

She: ‘Hey, buddy! Wanted to ask, why are you still single?’

Bachelor No. 2: ‘Baby, suddenly fancy me after all these years?’

She: ‘Shut up! I am doing a survey, dude.’ Bachelor No. 2: ‘Gussa ho gai! Your fault for asking such questions at this hour.’

She: ‘It’s 11 a.m., you idiot!’

Bachelor No. 2: ‘Oh! I am at a three-day rave in Goa, baby, lost track of time.’

Phone disconnected.

My turn again, and from the other end, a raspy voice answers, ‘I have already got a message about the daft survey you psychos are doing and I don’t want to be part of it . . .’ And he continues in his peculiarly self-important manner, ‘By the way, mummy forgot to send tandoori chicken today and my fund manager is coming over, so it’s good you girls called. Can you send a tiffin over please and send some gulab jamuns; my girlfriend is also coming, so send food for three–four people.’ As he pauses, I quickly interject, ‘Oh, your relationship with the seventeen-year-old must be going really well since . . .’ He screeches, ‘I am sick of telling you she is twenty-four!’ And hangs up.

The last man standing is now on the phone . . .

Me: ‘We are conducting an investigation. Can you please tell us, why haven’t you ever been married?’

Bachelor No. 4: ‘Has my mother put you guys up to this? I don’t want to talk about it.’

We persist till he finally tells us his story.

He was dating a Gujarati girl and one day in the grip of passion and wanting to emulate the West in this act, along with everything else, started spanking his girlfriend on the bottom, while saying, ‘Who’s your daddy? Who’s your daddy?’

The Gujarati girl, who I assume had never played this particular game before, called out shrilly, ‘Hasmukh Patel! Hasmukh Patel is my daddy!’

Unfortunately, my friend’s name is not Hasmukh Patel.

After that, each time he saw her in the buff, he would visualize her father: the pudgy, bespectacled Mr Hasmukh Patel and, in despair, had no recourse but to terminate their alliance. He has never been able to find the right girl since.

He sorrowfully recounts this story, and we commiserate with him till he bursts out laughing, and we realize that we have just been bamboozled.

These men have no tragic stories about losing the one that mattered, but are incredibly happy without what they see as the shackles of matrimony. While we feel sorry for them and worry about what they will do as they get older, they, in fact, feel sorry for us, as they see our lives as endless piles of diapers and suffocating predictability. Case closed, Dr Watson.

We put the phone down and though our lives are filled with all sorts of fulfilling things, talking to our old group again leads to a certain kind of wistfulness.

This is perhaps what middle age truly is— the future we dreamed about is a place that we now firmly inhabit, so we spend a little more time looking over our shoulder at the beguiling sepia-coloured postcards from our past where we once stood before an esoteric world of myriad prospects and were mesmerized at the possibilities it held . . .

R: Reaching for the Vomit Bag

The man of the house has summoned the entire family to Delhi where he has his next shoot. The prodigal son has a broken foot, the baby has a cough and I am down with a bout of insurmountable inertia—a strange malady that renders the sufferer incapable of making to-do lists, let alone pack 400 miscellaneous items that may never be needed.

I have had a very tough week and all I want to do is get into my bed, read sci-fi short stories and drink hot chocolate, but the new-age Indian woman’s work is never done because she has to do all the stuff that was dumped on men earlier, like dealing with doctors, talking to bankers, bribing random government officials, threatening accountants, and still has to change diapers, tolerate crazy mothers-in-law and jump at her family’s commands.

So when our son jabs me with his crutches and demands to know when we are leaving, I sigh deeply and simply do the needful.

THE PLANE RIDE: I am getting into the plane and I push all my eleven carry-on pieces, of differing sizes, including the above-mentioned crutches into various compartments, and settle into my seat only to find that my fellow passenger is another woman roughly my age, travelling with her husband, and a baby on her lap. Looking forward to exchanging stories and tips on babies and motherhood, I settle my limping warrior into his seat, plonk my baby on my lap and buckle up for the ride.

The plane takes off and my baby starts yelling. I am trying to make her drink water so that her ears pop open. The baby starts chewing the inflight magazine, the same magazine handled by hordes of people who may not all wash their hands after using the airplane toilet. I snatch it from her and console myself that perhaps the baby will have a stronger immune system because of this continuous exposure to germs.

The baby is now trying to bite the seatbelt, trying to bite my yellow handbag, hitting me on the nose with her genetically made-for-karate hands—generally making my life hell, as usual. The woman in the next seat who is still calmly holding her sleeping baby smugly, looks up, swishing her immaculate hair while staring at this spectacle. Just when I am about to burst into tears, I smell the unmistakable smell of baby poop.

Cursing my luck and wanting to take a parachute out of this plane, I struggle to get her diaper bag out of the overhead compartment, lug her to the bathroom, pull down her pants and . . . surprise, surprise . . . her diaper is clean as a whistle.

We come back to our seat and as the smell of fetid broccoli gets worse, I again pull her pants agape and peer inside. Nope, not a thing. And then it hits me: It’s the other baby next to us. Can the mother not smell it? It’s the grossest, most familiar scent to all us poor women who go through raising little monsters into semi-decent adults.

I keep staring at the other mom hoping she gets on with it, but to no avail. I try to chew mint in the hope that it will get the smell out of my nose. Nope, that doesn’t work either. Finally, just when I am about to give up, the woman starts sniffing around and, after peering at me—in what could be the longest ‘your baby vs mine’ standoff—pulls her baby’s pants down and there it is. She fumbles inside her Gucci bag and, to my mounting horror, pulls out a bottle of floral perfume, pulls the diaper down and sprays around the baby’s bum, Pamper and poop, and calmly p

uts the baby back on her shoulder.

All right, so now I am sitting in an aromatic cloud of shit and Chanel No 5.

Whoever said ‘Life is about the journey, not the destination’ needs to sit like me—covering my head with the in-flight vomit bag for the rest of the journey, while desperately awaiting my destination—before they spout some more philosophy. Au revoir!

S: So what’s Changed, Mommy?

Musings of a middle-aged, new mom

1. My bedtime: 8 p.m. was the time I would be relaxing with a glass of wine and planning what I am going to wear to tonight’s event. Now, this is the time I am fast asleep in my bed, drooling in an exhaustion-induced coma.

2. My various body parts: Sometimes I think the only thing keeping them in place is delusion.

3. My clothes: Will I ever wear my J Brand size 26 again? And more importantly, do I have any clothes free of baby vomit to wear today?

4. My man: From gazing at me worshipfully and declaring how beautiful I am, he now has one term to compliment me no matter what I wear: Cute! What the hell is cute? Am I a bloody teddy bear?

5. My brains: With an enviable tested IQ of 145, now there are days when I can barely remember what rhymes with twinkle. Sparkle? Spangle?

6. My peer group: I have always had savvy thirty-something-year-old friends, but now I find myself conversing with twenty-four-year-old other new moms, only to wonder if I was as dumb at that age.

7. My home: I have always had an immaculate, elegant home, but gone are the days when my living room could be featured in Architectural Digest; now it’s difficult to even find my sofa under mounds of diapers, swaddle cloths, burp cloths and bibs.

8. My food: My regular diet of dainty salads and grilled chicken is banned from my meal plans, as my mother-in-law is now force-feeding me ladoos, dry fruits and ghee-infused bajra rotis to increase my fluid output. I am secretly starting to think that this fluid output nonsense is just an excuse she has made up to make sure I never lose any weight.

9. My status: The man of the house has very politely informed guests who have come to see the baby that I am unavailable, as I am ‘milking’, and thereby sealed my status from cool chick to mooing cow.

10. My outlook: My vanity has taken a hit and my brains have been sucker punched, but what has really changed is the way I look at this body—from groaning about each lump and bump, judging my body by my dress size, I now marvel at the strength of this wonderful machine. It has produced two beautiful children, been terribly abused on occasion (apple martinis, anyone?), been neglected sometimes, but it has never let me down. Since it only responds to what I give it, with love, care, dedication and maybe a few starvation periods (let’s not kid ourselves to the contrary), I will perhaps sashay in my old jeans once again, while simultaneously determining the exact square root of pi.

T: Travel and Tyranny

8 a.m.: I am in a little, relatively unknown town in Germany; it’s an idyllic seaside small town where everyone knows everyone else and nothing seems to change. We come here almost every year or two to get the man of the house fit and ready to grapple with crocodiles and jump off skyscrapers.

10.30 a.m.: Waiting at the hospital for our turn in the physiotherapy department, I see a lot of people on crutches coming by as well. Each one limps in, calls out ‘morgen’ (morning in German) and everyone already sitting there answers back ‘morgen’; by the forty-third ‘morgen’ that I have had to cheerfully force out of my mouth, I want to put one leg out and trip the next limping soldier that walks in.

I do notice something that is rather strange. In the waiting area, we are around fifty people, all (besides us) over sixty-five and not one person has anyone accompanying them to the hospital.

In India this never happens—there is always someone to take you to the hospital. Even if your children live far away, there will be cousins, buas, chachis, even neighbours; someone always steps in. Looking at these old people shuffling along by themselves, all I can say is: We may have potholed roads but at least we have many people willing to travel with us on them.

3 p.m.: We decide to go to the nearest city, which is Hamburg, and I cajole an extremely reluctant man of the house to take a bus tour with me. In the movie business, we travel the world, but all we really see are our mirrors, hotel rooms and the shooting locations; so now that showbiz is far behind me, I am determined to see the world the way I should have all these years.

3.30 p.m.: We are sitting on the upper deck of the tour bus and our first destination is the red-light district of Hamburg. As the geriatric men in the bus are craning their necks, I make a few phone calls and get yelled at by my rotund, red-faced German tour guide, and am asked to go sit in the basement.

I start correcting him that a basement technically means a dwelling underneath ground level and even if I go below the bus and lie down between the tyres, I still won’t be in the basement, but the man of the house pulls my arm and uses this as a great excuse to end our city tour.

7.30 p.m.: The man of the house is not feeling too well and I decide to go down to the hotel restaurant by myself. It is a nice day and the restaurant is partially outdoor, so I decide to sit in the fresh air and enjoy a steak. I look around and see that almost every table is filled with people, most of whom have brought their dogs along for dinner. I like dogs, I have two German shepherds at home (pun totally not intended), and I wonder at their culture which is so different from ours, of bringing their pets everywhere with them.

There is a cute dog at the next table, and the owner, an older German lady, smiles at me politely and nods when I ask her if I can give her dog a piece of my steak. I throw the piece down and the dog gratefully laps it up, and before I know it, the German lady is telling me that if I don’t want to eat my steak, I should give the whole thing to her dog. I am not that hungry, so I cut a few bites, but suddenly my neighbour is giving me brisk instructions, ‘No, cut zee piece smaller, make tinier!’ I do my best and then she says, ‘My dog doezn’t eat salt, so pleaze suck ze pieces of steak, zhen feed her.’

So here I am, cutting my steak into bits, following instructions to make it tinier, popping each piece into my mouth, sucking the salt and finally feeding it to a dog.

I come up to the room in a fury and declare that I want to ban everything made in Germany, especially all these bossy Germans. The man of the house looks up from his iPad, sighs deeply and says, ‘Okay, darling, throw out our Siemens fridge, sell the Mercedes, tear up your Deutsche Bank chequebook, quit eating Black Forest cake, burn my Hugo Boss suit and toss away your Montblanc pen.’

I am staring at him in horror, awe and shock. He has never displayed his expertise in the area of general knowledge prior to this, and I stutter and ask, ‘Er . . . How do you know all these uhh . . . things are German and all?’

He smirks and says, ‘You are not the only one who can use Google, you know?’

Crap! Columbus has finally discovered America.

U: Undressed Under Duress

8 a.m.: I am walking on the beach with my sister-in-law when she tells me that she knows a good acupuncturist. The gentleman is my mother-inlaw’s old friend and since I have been moaning about a frozen shoulder that is not responding to physiotherapy and she has a knee problem that is also not getting any better, perhaps it’s time to try some alternative therapy.

11 a.m.: We have made an appointment to see the doctor. Amidst my giggles on discovering his name is Dr Luv, we confirm our presence at his clinic at 4 p.m.

3.45 p.m.: We are standing outside Dr Luv’s clinic. It is a dingy little building in the far-flung suburbs and before I can ring the bell, the door flies open and it’s the good doctor himself.

4 p.m.: The clinic is deserted, barring the doctor and a young oriental boy who is sluggishly dusting the reception table.

We start giving Dr Luv our medical history and soon enough he leads us to two tiny rooms and tells us to undress so that he can start our treatment. We try telling him that he can just jab the needles

in the required spots, but he gives us a big lecture about how, in acupuncture, one needs to heal and treat the entire body and not just the symptoms.

We are ushered into dilapidated, musty rooms. Through the wall, I whisper to my sister-in-law, ‘Why do we have to undress? What if there are cameras here to secretly film us? Let’s just find some excuse and run away.’

We decide to tell Dr Luv that I am unable to breathe, as I am allergic to mould and we will do the treatment some other time.

To our horror, the doctor looks unperturbed, and says, ‘I will come to your house and do the treatment.’

I stutter, ‘But your other patients? How can you leave them?’

‘Don’t worry!’ he says and calls out to the boy who is now dusting some shelves, ‘Aye, Nepali, listen! Kukreja will come at 5 p.m. for his treatment, usko bees pachees sui ghusa dena’ (shove twenty–twenty-five needles into him).

The Nepali boy looks shocked and terrified, but meekly nods.

4.45 p.m.: I am driving as fast as I can, but each time I look in the rear-view mirror, I see Dr Luv still following us in his dilapidated 1984 maroon Mercedes. I tell my sis-in-law, ‘God knows if the needles are sterilized! If we are forced to undergo this, at least let’s get some new acupuncture needles.’

My sister-in-law swiftly makes a few calls, and lo and behold, has organized new acupuncture needles to be delivered to the house shortly.

5.35 p.m.: Dr Luv has unfortunately not lost his way, and unable to stall him any more, I get ready for the treatment the same way a prisoner gets ready for the guillotine. Just in time, my sister-in-law rushes into the room with the fresh needles and a remarkable excuse, ‘Dr Luv, why don’t you use these needles? Someone gave it to me on Diwali last year and it’s just been lying here uselessly.’

Mrs Funnybones: She's just like You and a lot like Me

Mrs Funnybones: She's just like You and a lot like Me